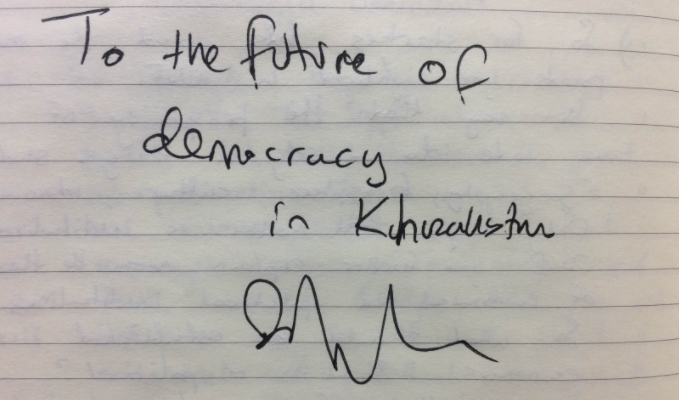

Economist Daron Acemoglu – about media and democracy in Kazakhstan

The Steppe: Mr Acemoglu, here, in Kazakhstan, you have many fans since “Why nations fail” has been published, and one of those is beside you right now. So, the main point of our talk will be about the concepts you and Mr Robinson have mentioned in a book. So, for starters, let’s count the main points you highlighted in “Why nations fail”: You say that the prosperity of any state does not rely on factors such as geography, biosphere, culture, knowledge. And the only factor that matters is the institutions. You further explain the theory of political and economic institutions, so which one of them should be established first for better prosperity?

Daron Acemoglu: Of course, there are some geographic factors that are important. Kazakhstan has oil and natural resources, for instance. But if we look at long run prosperity of a nation, it is really about the institutions. My mind is very simple. We live in a world in which there are boundless opportunities to create new products, services, innovations. But only society is that can provide broad best opportunities to the populations. If you take a society in the range only in a small fraction of the population is giving the opportunities that is like running a race with tens of pounds of weights tide to your back.

The Steppe: You also divide institutions into two types: inclusive and extractive institutions. What is the difference?

Daron Acemoglu: Inclusive economic institutions are those that provide this sort of broad based opportunities and the incentives, so there are based on private property and on a legal system that is able to uphold contracts and support economic decisions.

Daron Acemoglu: Inclusive economic institutions are those that provide this sort of broad based opportunities and the incentives, so there are based on private property and on a legal system that is able to uphold contracts and support economic decisions.

It is also has to be based on the ability of individuals to choose their occupations or the ability of entrepreneurs to choose their businesses and their ideas. And very-very importantly they also need to be based on a “level playing field”.

The Steppe: What does it mean?

Daron Acemoglu: For instance, you can ban 80% of the population from taking part in economic activities or you can choose not to provide them the high quality education or the same thing. That’s not a “level playing field”. That 80% want be able to productively part take in economic activity. “Level playing field” is important in having high quality of education system, health system, social mobility for all.

The Steppe: Well, all about inclusive economic institutions is clear. What about extractive economic institutions?

Daron Acemoglu: Extractive economic institutions are essentially opposite: lack of secure property rights, dysfunctional legal system. The state that’s not able to regulate economic activity, monopolize everywhere. And they are allowed to go while by a lack of government policy, for instance, or because of the distorting education system. Besides that, there are also the lack of infrastructure and other facilitating factors that make entire society to be able to take part in economic activity.

The Steppe: Let’s talk about political institutions. Could you please name how they are related with economic institutions as well?

Daron Acemoglu: The major point of the book and a lot of my research is that we can not have in a long run inclusive economic institutions unless we have a particular confluence of political institutional elements.

The Steppe: Is it about political institutions and democracy?

Daron Acemoglu: Yes, right. If you are going to go extractive economic institution, which favors the small fraction of a population, you can not have that full habit of democracy. Because the democratic society wouldn’t choose to just in reach a very small fraction of the population the expense of the poverty or the rest of them. By the other side of the same point, you are not going to be able to have in durable inclusive economic system, if political power concentrates in junta, or dictator, or autocrat or King.

The Steppe: So, inclusive political institutions require first democracy. What are other essential elements?

Daron Acemoglu: Democracy is the name of institutions. We need two other very important elements for inclusive political institution. One is constrained on how political power exercise. You can have elections, which according to the most efficiency up to by democracy, even if they could be taller free and fair. But then you elect somebody and make him or her the King for the next five-six years and they can do whatever they want. To some point, you then cannot constrain how this political power to be delegated.

The Steppe: How can we get this term?

Daron Acemoglu: It means there will be following basic exercises as:

- Supreme court, a legal system that able to be sit above the president, above the parliamentary system and stop them

- Separation of powers

- Media that is free

Civil society that constantly check the power. And for instance, if they don’t like something, they can’t be lowed, they can be protested, they can go to streets, they can write articles.

The Steppe: One of you current joint publication calls “Social mobility and the stability of democracy”. You mentioned this when we talked about economic institutions and democracy. I guess your researches in this field are very impressive. From which point are you examining this issue and when are you planning to publish this research?

Daron Acemoglu: Democracy is one of the elements of inclusive institutions. It’s been a particular focus on my research, and a paper that you have refer to with is part of a serious papers I try to understand theoretically and empirically, what are the factors that enable democracy to function very well. So an idea that goes to top claims that the democracy works much better when there’s the social mobility. But you also have to worry about some types of social mobility, especially those that make the middle classes expect to lose their economic standing. Because that sort of social mobility, that sort of downwards of a middle class might actually destabilize democracy. Articles that I write are for academic journal, but many ideas make the way of bigger volumes like “Why nations fail”, and, hopefully up come some point.

The Steppe: We hope so. It is hard to predict, but could you please say: in 10-15 years, which one of these two types of institutions will be the dominant and most widespread form of institution?

Daron Acemoglu: Going back to Hegel, what thought was prevalent in 19 century, or German philosopher Marx, — democracy is being brought automatically to greater spread around the world. My empirical research and our overall conception do not support that. Sure, inclusive economic institutions supported by inclusive political institutions are better for society.

But I don’t think in the concept of the next 50 years we are going to see the world overtaken by inclusive political institutions. It is a very-very difficult process. You see that democracy is being badly manipulated in many developing countries from Turkey to Hungary and Malaysia. And part of that is lack of free Media. Civil society needs is very keeping politicians in check, but civil society can only get information. And you chock the Media, and it doesn’t work. And many autocratic leaders have noticed that, and have really started undermining democratic institutions all over the world.

The Steppe: You think there are going to be less democracy in the world in the nearest future, don’t you?

Daron Acemoglu: I would not be surprised, if in the next fifty years, we are in a situation where fewer countries then today are actually democratic and reverse at democratic trends. But I think also there are positive trends, because we live in a globalized world, and information is very difficult cut up in a single country.

The Steppe: How could you estimate Kazakhstan’s reality in terms of institutions?

Daron Acemoglu: As I mentioned previously, it is very complicated question to transition extractive political and economic institutions into inclusive political and economic institutions. That’s one that I think Kazakhstan will have to confront in the next several decades. And it’s going to be a challenge. It’s going to be a very difficult process.

I see a lot of optimism here, that’s great, but I think that optimism is a little too optimistic.

The Steppe: So where do you see the subject?

Daron Acemoglu: The demand for change come from the bottom, but in many societies, for example Kazakhstan included, you do not have that problem. First of all, it’s about civil society. I look it in the Media, I looked it in the newspapers yesterday and today in Kazakhstan, there’s not the single news, everything says “Official government said that, official government said this”. I mean you can have civil society and private sector, have a political presence in a society where the Media is like that. Civil society is closely integrated with government, and private business is so integrated with government. So you see right now several reforms. I think some of these reforms are in carriage. But it is about the partnership between civil society, private business and the government. And right now there isn’t a partnership, there’s a Big brother and there are everything and private business is not even a “little brother”, it’s like a servant. Civil society is not even to be seen. So I don’t think that works. That is one challenge. The other challenge is that once you have a tradition or this sort of dominance of a single leader, or a single party, when finally some segments of a society founding voices that put on the hand. We have seen it in Libya, Syria, Egypt. That creates polarization, where everything is much worse.

The Steppe: But there are some examples of successful transformations with no tragedy. How can you explain that?

Daron Acemoglu Sure.

If you look in successful cases of building inclusive political institutions, they had this very happy medium in which civil society was bold after make claim. The political system did not want to use a repression because requires were reasonable, demands were reasonable.

You have protest, but you don’t have those protests turning to bloody repressions. You have extensions of trend or strength of democracy that might sometimes be bold and loud. But not civil war. So by look at Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan has make some attempts in that direction. But it’s again a very difficult happy medium to sort of create. Kazakhstan probably may be the next successful case in regard. I think Kazakhstan has big-big challenges of this not easy process.