Takaharu and Yui Tezuka: Architecture is not about comfort — it’s about learning how to live

In mid-October, Almaty hosted the international symposium Schools for Future: From Knowledge to Wisdom — a rare gathering where educators, architects, and philosophers came together to imagine the school of tomorrow. The question was simple, yet essential: What kind of schools allow a child not to lose themselves, but to unfold?

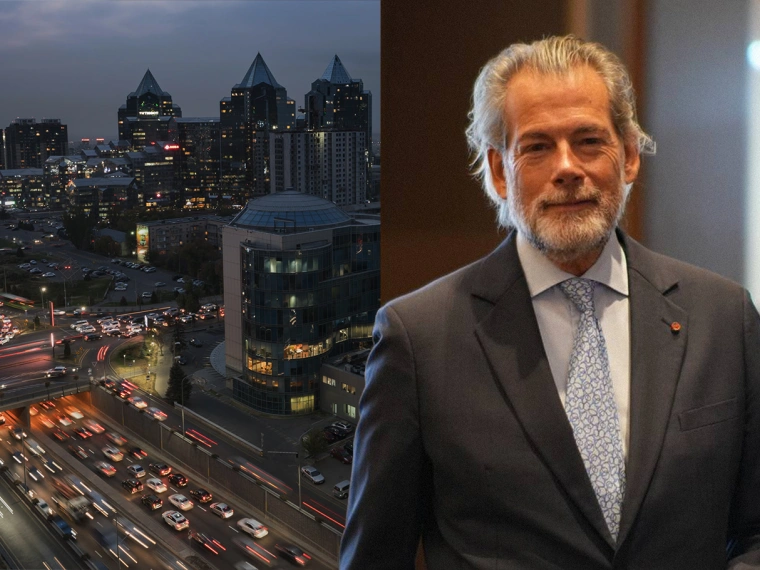

Among the speakers was Takaharu Tezuka, one of Japan’s most celebrated architects, known for designing spaces that breathe, bend, and listen. His Fuji Kindergarten — a circular, open-air building without walls or corridors — is often called the happiest school in the world. In Tezuka’s view, architecture isn’t a structure; it’s an act of empathy.

In this interview by STEPPE, the Tezuka family speaks about discomfort, nature, and why architecture should be alive.

Many describe your architecture as child-centred — that everything begins from the child’s point of view. How do you actually approach this idea when designing schools?

It’s funny — people often say, you put the child in the centre. But I never said that. I don’t think architecture should put anyone in the centre. Life itself has no centre; it moves.

What I do believe is that architecture must not get in the way of children. It should give them the freedom to decide how to use it.

Children are already intelligent. They know how to explore, to climb, to make noise. We don’t have to teach them curiosity. We only have to create spaces where that curiosity can survive.

So your role is to design the conditions for discovery rather than to design control?

Yes. The modern world is obsessed with comfort and control. But when everything becomes convenient; the perfect chair, the silent corridor, the automatic temperature — people stop thinking.

Discomfort is not a failure. It’s a form of education. When a child tries to move a heavy table, they learn about gravity. When they drop a ceramic cup, they learn what fragility means. Plastic never breaks — so it never teaches.

Of course, equality in education matters. Every child should have a place to learn. But equality doesn’t mean comfort. Sometimes, the small inconvenience is what makes a human being more complete.

That sounds almost philosophical — as if the physical space becomes a teacher itself.

Exactly. The space is a teacher.

If you design a room that tells a child what to do, they will obey. If you design a space that gives no clear instruction, they will imagine. That’s why at Fuji Kindergarten there are no walls, no corridors — just an open circle. Children run, get lost, find their friends again. They learn not through instruction, but through interaction. Chaos is part of nature. You can’t separate children from that.

Many parents today seem to want the opposite — minimalist rooms, everything beige and quiet. They say it helps focus.

If you put children in a white space, nothing happens.

And if you fill the same space with bright artificial colors — it’s the same problem, only louder. Both are artificial.

If you put a child in the forest, they will start to explore immediately. The ground is sometimes wet, sometimes soft; the light changes every minute. They learn to adapt. That’s real design — when life itself becomes the material.

We need spaces that breathe with nature — not imitate it, not decorate it, but coexist with it.

So color and decoration mean little compared to the presence of life?

Yes. Color doesn’t teach. Change does.

When you open a real window, and the sunlight shifts during the day, that’s education. Children feel the passage of time; they see that the world is not fixed.

Artificial light, artificial surfaces — they don’t bring messages. Natural light does. When you can see the dust in a sunbeam, or hear rain hitting the roof, you begin to understand that the world moves with you. That’s wisdom, not knowledge.

You often say architecture should be “symbiotic.” What do you mean by that?

Architecture cannot exist alone. It’s not a sculpture. It’s a species. A building must live with its surroundings — with the wind, bacteria, sounds, even discomfort. We humans are part of this ecology, not separate from it.

That’s why I make a distinction between nature and natural.

Nature — the wild world, is too strong for us. There are bears, storms, hunger. We can’t live in it.

Natural — that’s when we cultivate a balance. We tame just enough to survive.

In Japan, we call a jungle yasei, and a forest mori. The jungle devours you; the forest shelters you. Architecture should be like a forest — something that protects but never isolates.

You saw some of Almaty’s architecture this week. There’s a glass skyscraper shaped like a mountain — meant to imitate nature. What do you think of that?

That’s not the best way to understand nature.

If you simply copy the shape of a mountain, it’s no longer a mountain. If you copy a bear, it’s not a bear. Nature is not really about imitation — it’s about essence.

Architecture can draw inspiration from nature’s meaning, rather than form. A mountain moves us because it’s vast and humbling. When that feeling is translated into space, the result carries the same quiet strength and respect. In this way, architecture doesn’t reproduce nature, instead, it resonates with it.

We must remember: the sublime — that feeling of awe — is essential to human experience. Without it, architecture is only geometry.

So, for you, meaning matters more than form. How do you define meaning in architecture?

Meaning comes from life. From memory.

Imagine you drink tea made by your grandmother. Maybe it’s not the best tea, but it’s the most meaningful. It carries her voice, her hands.

Now imagine the same tea from a factory — maybe it tastes better, but it has no story.

That’s how I see buildings. Old temples in Japan are inconvenient — freezing in winter, humid in summer. But they have life inside them. Each one holds a thousand years of footsteps.

Meaning cannot be built; it has to be lived.

If you could choose between an ancient, uncomfortable home and a new, efficient one — which would you live in?

You don’t have to choose. Modern life allows us to have both — technology and memory. My own home is more than 400 years old, a listed building. It connects me to my ancestors. But I also use an iPad and take airplanes. I exist in both times.

We shouldn’t see technology as the enemy. It’s invisible support — like air. The danger is when it replaces our senses.

That’s why I love the phrase “nostalgic future.” We move ahead, but with the wisdom of what has already existed. It’s not a cycle — it’s a spiral.

That’s a poetic idea — a nostalgic future. Is that where you see architecture heading?

I hope so. You know the movie The Matrix? Or Tron? They both tried to imagine the future — all neon lines and metal worlds. But the real future is invisible. It exists in the air between you and your coffee cup. It exists between two people talking.

As technology grows, what we crave is not more data but more humanity.

The more digital our world becomes, the more we will long for wood, for sunlight, for imperfection. That’s the future I believe in — one where technology quietly serves our senses instead of replacing them.

And if you could describe your “ideal” building — one that holds all your philosophy — what would it look like?

It would not look perfect, It would be alive.

We’ve been trying to build that all our lives — spaces where people can feel the rhythm of existence. A child running, an old person resting, wind passing through.

But I am not an artist. Artists can do whatever they want. Architects live within reality — among people, among children. We don’t create for ourselves; we create for life to happen inside.